Having recently retired after a number of years as a staff engineer for a very fast-paced company in the tech biz, I thought that taking a few days for a bit of a hike would probably be just the mental break I was due for to catapult myself into the idle future. The only question, then, was where I should go.

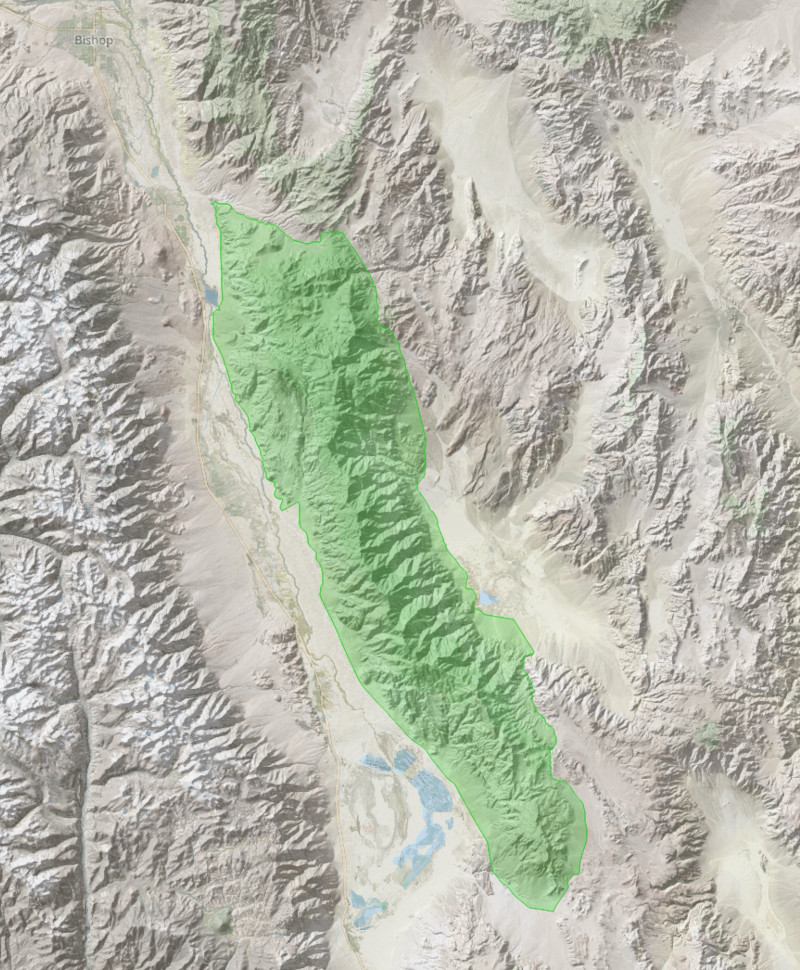

As detailed elsewhere in this blog, we recently moved to Independence, CA, on the Sierra Eastside. Out of our main window, we can see a portion of the crest of the Inyo Mountains, the range on the east side of Payahǖǖnadǖ (née Owens Valley), thus making it the obvious destination, nevermind that there are no trails or roads that follow the entirety of the crest, and that it’s rugged and dry.

My plan, then, was to spend as many as eight days traversing the crest of the Inyos, or as close as practicable, from Highway 190 in the south to Death Valley Road in the north.

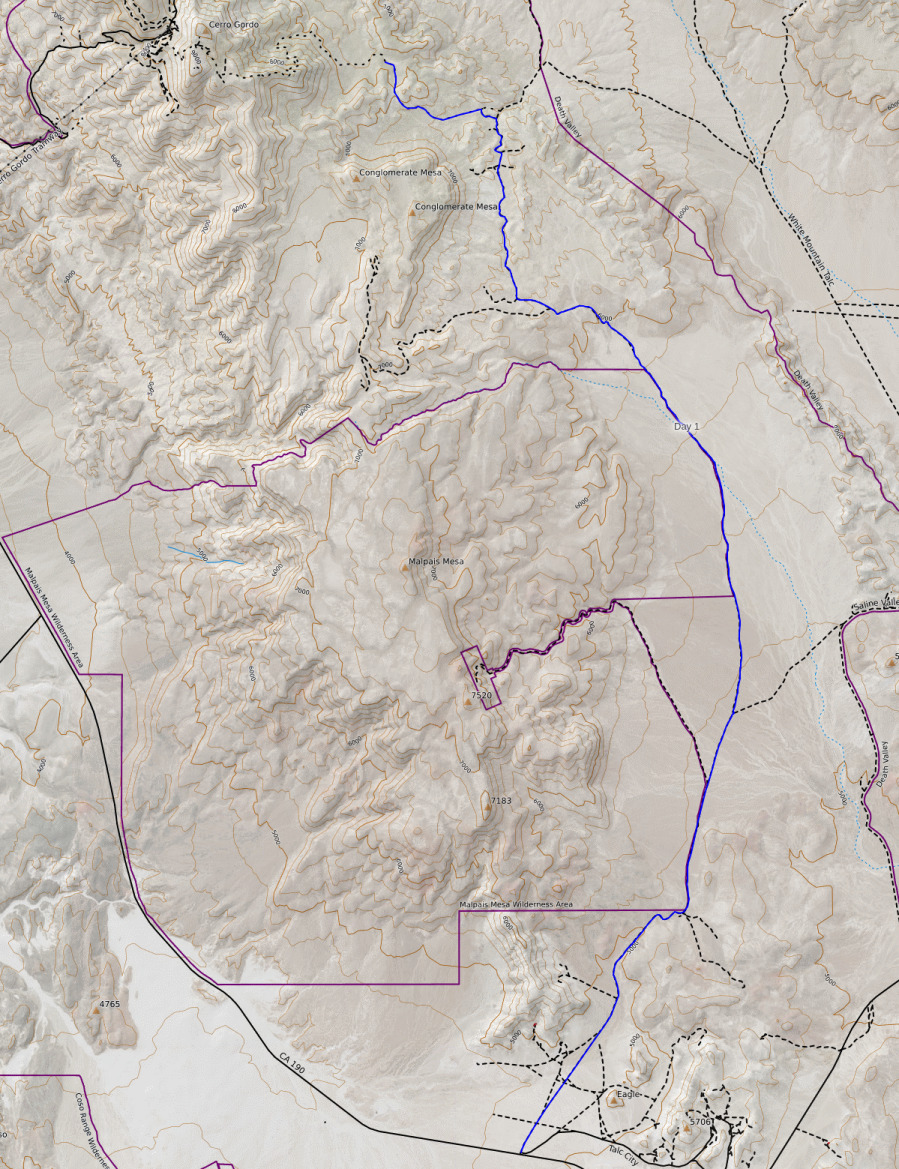

From Highway 190 to New York Butte, there are a number of dirt roads that can be pieced together to form an easy-to-follow route. And also from Badger Flat via Papoose Flat to Death Valley Road, there are dirt roads. From the end of the road at New York Butte, I was aware of use trails along the crest all the way to Mount Inyo, made over the years by peakbaggers. So the only truly off-trail section would be from Mount Inyo to Badger Flat, and I know that the section from around Winnedumah-Piute Monument north is passable fairly easily, leaving just the middle section as a large question mark (or “adventure” as I would have it).

Water was bound to be a problem. I’m aware of five springs close to the crest, from south to north: Cerro Gordo Springs, Mexican Springs, Goat Springs, Seep Hole Springs, and Side Hill Springs. Seep Hole Springs and Side Hill Springs are confirmed to be flowing, and those are all in the northern half. So for the southern half, I decided to carry two additional gallons of water, and then hope that any of the three springs in the south would have enough to get me to a cache I’d placed at the crest along the Pat Keyes trails.

While planning, I was fortunate enough to meet a fellow who’d been roaming all over the desert for many decades. He showed me his 7.5″ maps that he’d annotated the location of the Lonesome Miner Trail (he’d hiked it before it was given that moniker back in the 90s), and I took photos and then transferred it onto my own 7.5″ topos. Aside from the trail, I also got notes about the location and quality of springs on the east side of the range. While these were all far off the crest (just a few miles laterally, but many thousands of vertical feet down), this greatly expanded my alternatives should the springs at the crest be dry.

As the chosen date approached, I gathered my gear and supplies and prepared. 3/4 gallon of drinking water per day (the temperatures were still moderate at this time of year), with the remainder of the gallon for rehydrating breakfast and dinner. Eight dinners, eight breakfasts, and 2000 or so calories for lunch and snacks per day. I’d bring along two one-gallon water bags for carries in between sources. And, of course, the usual camping gear: tent, pad, lightweight quilt, warmer clothes, one clean pair of socks per day (luxury!), and a spare shirt.

Day 1

The first day had the most mileage, but, then, it should have since it was mostly gently uphill. I walked from Highway 190 at Talc City Road to a nice campsite southeast of Cerro Gordo, just before the big climb up to the crest proper. This was about 18.4 miles with +2500/-500 feet.

While a true traverse of the range would have gone over both Malpais Mesa and Conglomerate Mesa, that mostly trail-less and rugged country would take me much longer to hike than the road-based route I chose, and the location of the next water source was still very much a question mark at this point. I do plan to visit both in the not too distant future since they look, from a distance, as exactly the sort of desert terrain I most favor.

Robin dropped me off at the start point, and then rushed off to tend to the audibly leaking tire her car developed on the way.

The first twelve or so miles was a straightforward stroll up a nice dirt road through Santa Rosa Flat with a mellow incline. Around mile 6.5, there was a fork in the road. Right led to Saline Valley, and left went my way. There had been a benchmark placed around that fork, but it’s missing now, and the concrete block it was set in looks like someone took a sledgehammer to it. I expect some kind of treasure-seeking yahoo decided to steal the benchmark as a monument to their idiocy, not much different from the sorts of folks who pillage archaelogical sites anywhere there is historic junk to be had.

By and by, the road took took a jog, first to the west, then to the north, and led along the foothills of Conglomerate Mesa. By this time, the joshua tree forest had become a mixed joshua tree / pinyon pine forest as the elevation steadily rose. Clouds that had been threatening precipitation delivered; first with a little rain, then with a little graupel. Fortunately, this being the desert, I dried off as fast as I got wet.

After 16 miles of hiking, I turned left at a T to head up the valley between Conglomerate Mesa and the Cerro Gordo massif. This was the road that led at one point to the old Belmont Mine, and would take me up to Cerro Gordo peak. But it was getting late in the day, so I stopped at an old campsite before I had to begin that climb.

After a warm dinner, I retired to a very cold night. The combination of lots of calories burned, cold temperatures, and not enough room in my pack to bring more warm clothes made for much shivering.

Day 2

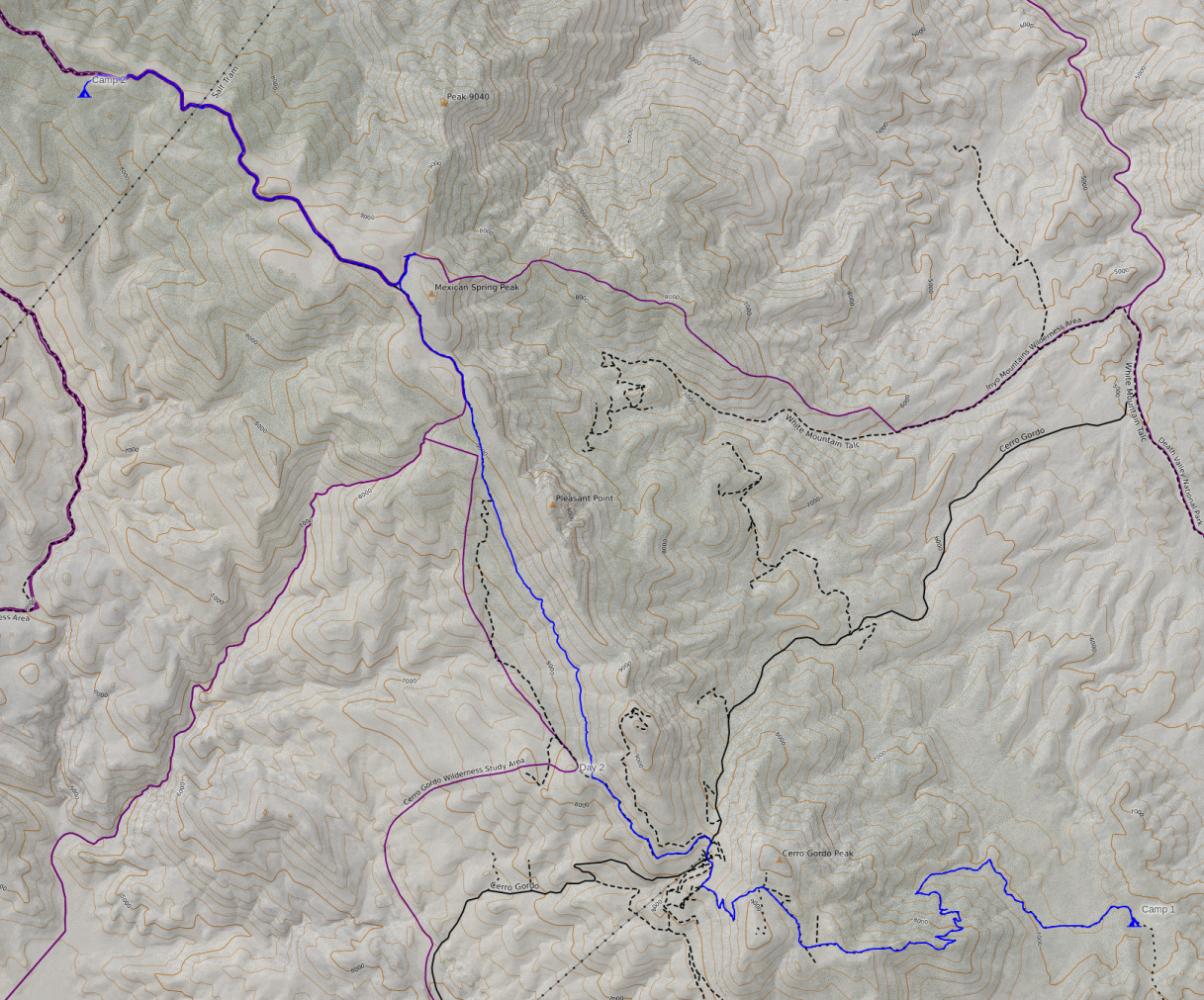

The second day was a tour through mining history, from the debris of Cerro Gordo, to the Salt Tram summit station. It was about 14.4 miles with +3900/-2300 feet of elevation.

I began the day with a hike uphill, marveling in the views to the north into Saline Valley and of all the desert ranges beyond. The road was likely built to service the Belmont Mine. What they were mining and how successful they were doing so is unknown to me, but the road they left was convenient.

Once to the mine proper, the road devolved into a single-track. It seems that folks on dirtbikes go through every so often, but I doubt there’s much human presence here otherwise. This road popped me out onto a ridge with a road that led to the vicinity of Cerro Gordo peak.

I descended down the service road into Cerro Gordo proper. The current owner of these ruins advertises them all over various social media sites as a “ghost town” and such, and has done a good job of stirring up interest from the too-online set. The reality of it, though, was rather surreal for me. From remote desert mountains into a horde of people and four wheel drive vehicles, complete with alpacas(?) and what looked to be a gift shop.

Fortunately this passed by soon enough as I headed north along the “Swansea Salt Tram Road”. This road has a reputation of being terrifying for passengers, with the one track higher than the other on some steep hillsides, giving the appearance that the vehicle might roll off and down the hill at any second. But it’s quite tame to walk on, and I made good time to my next fork, onto the Cerro Gordo pipeline trail.

When Cerro Gordo was a booming mining town, well over 100 years ago, lack of water was continually an issue. It was mostly hauled up from the valley below at great cost and effort. One enterprising fellow hauled it in by mule from Cerro Gordo and Mexican Springs to the north and charged by the gallon. Eventually, enough investors were hornswoggled into funding a pipeline from those very springs. The remains of this pipeline and associated pumphouses is still there, and you can walk along the remains of the pipeline road as you traverse the side of Pleasant Point. The alternative is to continue to follow the main road as it drops way down, then climbs right back up again.

The pipeline trails itself is fairly easy to walk along. There are one or two sections that look a bit precarious, but are still holding to the hillside some how. Along the way are ruins of pumphouses, and old shutoff valves sticking out of the ground.

Once past the pipeline trail, I rejoined the road and headed up to the crest. A short distance further and I could see the remains of the pumphouse at Cerro Gordo Springs, but no easy way down. So I continued to Mexican Springs a short ways north.

I found the springs alright, but it was clear no water has been there in many years. Be it from damage to the infrastructure or from climate change leading to more dry years than wet in the Inyos, this springs is now a relic.

What this meant to me was that my next hope for water was to be had the next day at Goat Springs, north of New York Butte. I had enough water to last me until the following evening, and I was appreciating the lighter pack (especially with the now angry blisters I was developing from all the extra weight I’d been carrying).

After the spring, the road continued more or less along the crest to the next place of interest: the Salt Tram summit station.

Saline Valley, east of the Inyos, contains a large “lake” (really just a damp salt pan). Enterprising miners descended in the 1800s to extract as much as their mules could carry. The richness of the salt deposit there allowed yet another group of investors to have their pockets lightened to fund what’s probably the most ambitious tram ever built. This salt tram carried buckets of wet salt from the deposits in Saline Vally, up 7500 feet or so over some of the most rugged mountain terrain anywhere, then back down 5000 feet to the shores of Owens Lake, where it was barged across to the railhead (this was in the days before Los Angeles drained the valley dry) and shipped away. All of the tram towers still exist, and cable is still strung between most of them. The construction of these was a feat and documented elsewhere on the internet. The summit station and associated caretakers cabin have been preserved and, if you can make it there, are free for the exploration.

After looking around a bit, I continued north, intent on finding a place to camp for the night. I saw on old spur road on the map that seemed to fit the bill, and once I got there, it did indeed. I continued past where it had been closed off years ago to a nice old campsite with lovely views.

After yet another warm dinner, I had yet another very cold night. Next time, I’ll try to find room in my pack for something warmer.

Day 3

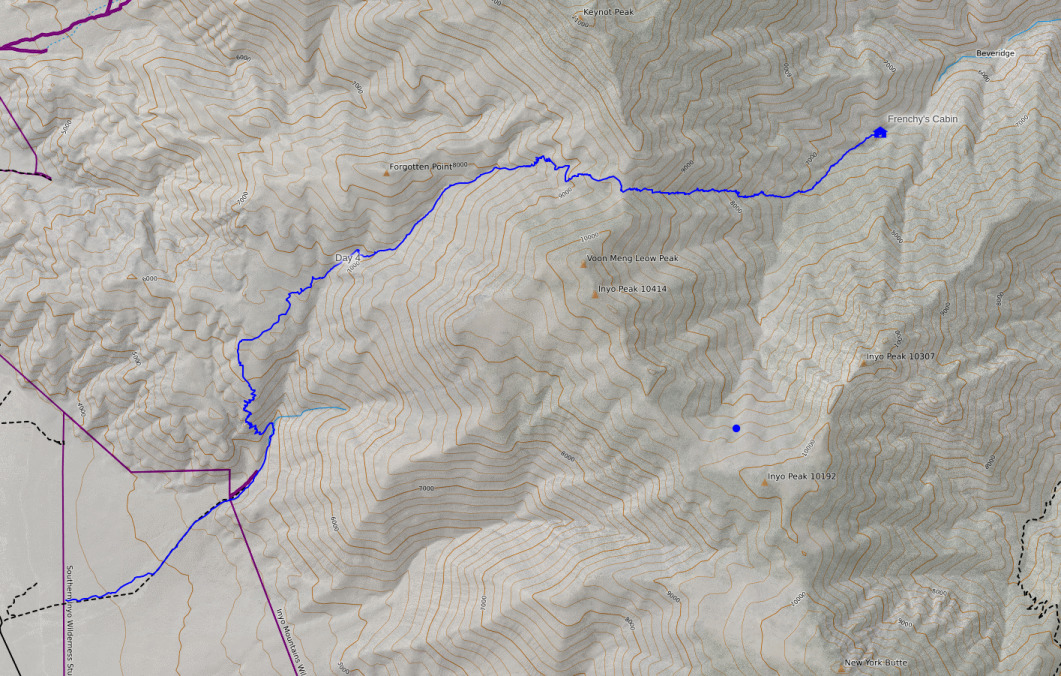

The third day of the trip didn’t end up exactly where I expected. One more dry spring meant I had to head off the crest to the nearest reliable water, down in Beveridge Canyon (ha!) at Frenchy’s cabin. This day was 11 miles with +2600/-4600 feet of elevation change.

Since I was down to less than a gallon of water at the start of the day, I knew I would have to get water or bail this day. The next potential source was Goat Springs. I had read online that some folks had found a small amount of water a few years back, so I had some hope.

But first I had to finish traversing the road section in the south half of the trip. I was very much looking forward to getting to the more wild section of the trip (though even with the road, the Inyos are still far more wild than any trail in the Sierra).

The walk north was quite scenic, with the road staying to the crest by and large. Unfortunately it was rather blustery that day, so walking along the crest exposed me to quite a bit of cold wind. Still warmer than I had been the night before with relatively little wind, at least.

I passed the turnoff to Swansea, and then quickly finished the short distance to the end of the road by the Burgess Mine. Interestingly, one start of the Lonesome Miner Trail forks off from around there along an old road into Hunter Canyon.

The trail up and over New York Butte was a nice single track use trail that continued over the shoulder and all the way down to a saddle below. I had a nice lunch at one of the most pleasant spots I’ve sat around in. It probably wasn’t too special, except that my legs were tired and my feet hurt, and it was warm for a change and otherwise pleasant.

Then up and along the ridge, still following a use trail until I lost it just above Goat Springs.

Once I got down to Goat Springs, I made a couple of discoveries: First, the spring was completely dry. And second, the report of water was almost certainly referring to some rain water still sitting in the catchment barrel.

I had a choice to make, then. I could try to be extremely ambitious and just go for it, hoping I could make my water cache that night. I could head down canyon to the east to Frenchy’s cabin where there were many reports of plentiful water. Or I could bail down the Forgotten Pass trail (sometimes called “French Spring Trail”) and call Robin to come get me.

The first option, gunning for my water cache, wasn’t a good one. It was still many miles over the tallest peaks in the range on not very good use trails. And my legs were tired, it was past mid-day, and my feet hurt. Besides, my water cache was only one gallon, and that would leave me with very little to spare (or none) and fewer bail options once I entered the trail-less portion to the north.

The third option, bailing entirely, was premature. I still had a water option, and plenty of food. Plus, the 6000 foot descent was extremely unappealing. And besides, why bail at the first sign of trouble?

So that left the second option. Aside from the additional distance and elevation, it was actually somewhat appealing. I’ve been wanting to explore the very remote east side of the range, and this was a good opportunity. If there turned out to be no water at Frenchy’s cabin or below at the Beveridge town site, or at the nearby Cove Spring, all of which are reputed to have good water, I’d just have a very long and thirsty trip out the following day.

So down I went. The trail was an old pack trail from the mining days, well over 100 years old. Rough in many spots, but passable and steep. It first descended the hillside, and then followed the bottom of the canyon for a few miles.

Just when I was starting to get really tired, I rounded a corner and happened upon Frenchy’s cabin. And just on the other side of it was a pipe coming from above with water gushing out into a metal bowl and birds flitting about.

I have no idea who Frenchy might have been, but I do know that the cabin he built is a marvel. The back wall is just the granite cliff it is up against, no doubt carved out somewhat. The other walls are large granite blocks, stacked eight feet high. There are two rooms. The main room has two bunk beds, one old (original?) cot, and a fold-up cot. There are mattresses hanging from a wire (to keep varmits out). It has a small woodstove, and lots of tools and supplies for doing trail maintenance nearby.

Outside is a fire ring and benches, and past the pipe is a small stream with water flowing by. There’s a register with entries going back many years. Lots of fascinating tales are in there!

Once I got there, put my gear down, and drank my fill of water, I had to take stock. I’d been developing blisters since the first day on my feet from the impact of too-old shoes and much more weight than I was used to carrying (water is heavy!). I had been fine enough along the crest, but the steep descent to the cabin had been brutal, and every step was painful. Knowing that the hardest and most delicate walking was still ahead of me, I decided I should just bail the next day, leaving the northern part of the trip for the future when my feet were tougher and I had more water cached. So I sent Robin a message via my satellite tracker to come pick me up the next day, and then settled in for the coziest night I had by far.

Shortly after I got into bed, I heard a rustling, though. When I turned on my light, I saw the cutest mouse sniffing about, wondering how to get into my pack. It wasn’t afraid of me in the slightest, so I spent the next little while trying various ways to put my pack where it couldn’t get to it. I ended up hanging it from the wire with the mattresses and had no further interruptions.

Day 4

All I had to do on the fourth day was to haul myself up and over Forgotten Pass and down to the valley, where Robin would come to drive me away to the ice cream shop. But, Forgotten Pass is actually a bit unforgettable; aside from a commanding position astride the Inyo crest, the trail is rough and the elevation gain is enormous. 9.7 miles and +3300/-5900 feet.

I packed up for the last time, drank a bunch more water, and filled my bottles for the arduous trek home. I backtracked partway up the trail I came down, looking for the junction with the Forgotten Pass trail. I hadn’t noticed it on my way down the previous day, but I knew about where it should be.

It turned out to be exactly where expected. Unfortunately for me, that was at the bottom of the canyon that, when I first saw it, I thought, “wow, that looks way too steep and short to be the one.”

Steep and short it is. The trail has been beat up a bit over the years, too. Trees have fallen across in places, and a few slides have covered small portions. It’s still quite easy to see, just brutal to follow. The east side is just plain steep.

I finally made it to the pass, and had to sit for a while to take in the view. You can see mountains forever on both sides of the pass. It’s well worth making the trek just to sit there and gawk.

But gawking wouldn’t get me home, so down I went, feet hurting every step of the way. The trail on the west side is in better shape (likely because it’s less steep), though still rough. Eventually it deposits you next to a scoured out stream bed that you follow for a ways.

I saw my first people in a couple of days as I was about midway down. This was a sizeable group (6-8?) heading up and over to Frenchy’s cabin. I chatted for a bit and kept going.

Eventually the trail climbed back out of the canyon to finish along a ridge. Robin and I had hiked this a little while before, and it felt good to be on familiar ground.

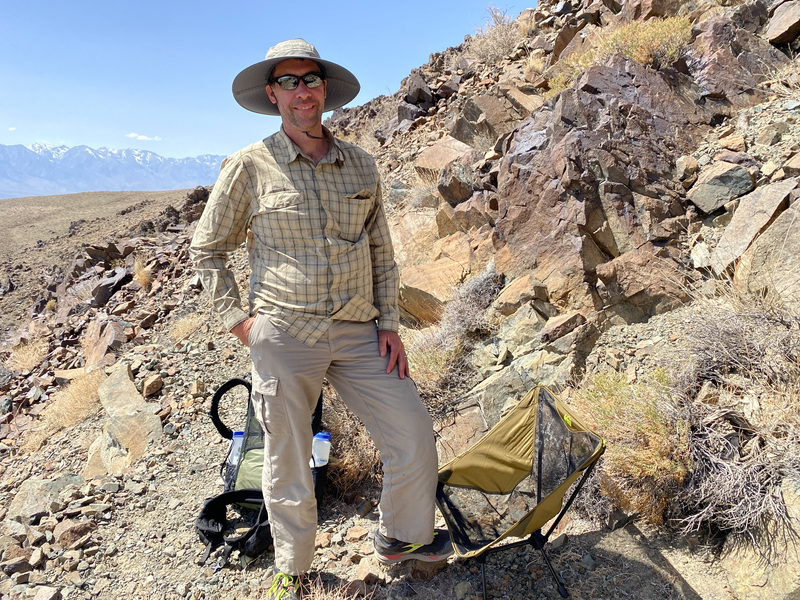

Farther down, who did I see on her way up the trail, but Robin! She brought water (still and sparkling, both cold), snacks, socks, shoes, sandals, and my camping chair! We headed down to a convenient spot, where we put my chair together and rested a while. Very nice!

We then packed up and headed down the rest of the way to her car. Then back into civilization. First stop: Eastern Sierra Ice Cream Company!